COOPERATION BETWEEN ALGERIA AND THE EUROPEAN UNION ON PRISONS: 10 Years of Support for Prison Reform

This year marks the 10th anniversary of cooperation between the European Union and Algeria on prison reform. The results of this collaboration regarding the implementation of sweeping reforms of the prison system were discussed on 8 October 2018 during a conference in Algiers.

Adib stands proudly in front of his workshop where he crafts handmade shoes. As the delegation, led by the Director of the Algerian Prison Administration and the European Union’s Ambassador in Algiers, pass in front of the small stand where he displays his creations, he hardly looks disturbed.

“I am the first craftsman to make shoes and sandals with thread, a technique that was invented long ago by Iraqi fishermen using their fishnets on the banks of the Tigris and the Euphrates,” he explains, showing the seams of a pair of sandals. At 44 years old, Adib, who spent many years in Iraq, admits that he has “come a long way”. “I served a few months in prison for a simple administrative problem – a family misunderstanding that turned sour. But when I was released, I received support from the Prison Rehabilitation Service which helped me get a loan to open my small workshop. Today, I make quite a decent living from my job and I have even been able to train young people in this technique.”

Rehabilitation

Adib is part of a group of ex-convicts asked to share their experience at a conference held on 8 and 9 October in an Algiers hotel entitled “10 Years of Algeria-European Union Cooperation on Prison Administration: Results and Prospects”. Through its involvement in two major programmes, the EU remains a significant partner of the Algerian Ministry of Justice and the Department of Prison Administration and Rehabilitation (DGAPR) in the reforms to its prison policy launched in 2005.

Youcef, younger and more reserved than Adib, also shows off his craftwork. As an artisanal metalworker, wrought-iron banisters are among his creations. “I left school when I was young, and I never got the chance to enter a vocational training programme. I was in prison from 2013 to 2015. I won’t say it was a good time, but I was given the opportunity to receive training in metalwork and ironwork. As soon as I was released, I received assistance from the Rehabilitation Service which helped me get support from the National Agency for Youth Employment (ANSEJ) and obtain a bank loan to cover the costs of a workshop,” Youcef says. He too believes that his “rehabilitation” was a success.

The issue of rehabilitation is a central component of the prison administration reform. The Rehabilitation Service has offices in each province (wilaya). As part of their mission, they meet with the convicts eligible for release 6 months before they leave prison. If the individuals agree – there is no obligation – they get in touch with the rehabilitation service, which provides rehabilitation assistance that corresponds to their profile and the courses or training they received during their time in prison. “The rehabilitation service can assist convicts in their job search or in getting a project off the ground,” explains Slimane Tiabi, Educational Director at the Algerian Department of Prison Administration and Advisor on the Algeria-Italy-France Institutional Twinning funded by the European Union to provide “assistance in strengthening the prison administration”.

A Remodelled Prison Policy

President Abdelaziz Bouteflika began the reform process in 1999 during the first year of his first term. “The general principle underpinning this modernisation was first expressed by the National Commission on Judicial Reform established by the president. In their report, the Commission’s members underscored the fact that convicts were among the foremost victims of human rights violations. It must be said that the state of our prisons left much to be desired. We had a serious problem of prison overcrowding, in buildings dating back to the colonial era. These prisons were dilapidated and totally unfit to house convicts with respect for human dignity. The general public also had a very poor opinion of the prison system,” acknowledged Mokhtar Felioune, Director of the Algerian Prison Administration.

The first major step in this reform was to draft a specific law for prisons. The Code on Prison Organisation and Convict Rehabilitation was enacted by the Parliament of Algeria in 2005. “Our first major step in the reform was recruiting and training new personnel. To give an idea of the changes, before 2005, only 70 psychologists worked in Algerian prisons. Today, there are over 500. Wardens have also been instructed to open classrooms in their prisons to allow convicts to continue their studies,” Felioune adds.

Expertise

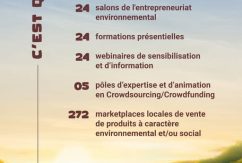

To carry out its reform project, Algeria needed to enlist the help of other countries to learn from their expertise and experience. The European Union provided this assistance to the Algerian government in 2008 through a “Programme for Supporting Prison Reforms in Algeria”.

This programme – with a budget of 18.5 million euros in European funding, 1.5 million of which came from Algeria – ended in 2014. “This initial programme allowed for better social and economic rehabilitation of ex-convicts, improvement of prison conditions, better training of prison personnel, modernisation of the way prisons operate and maintain security, and reorganisation of the prison management system,” Slimane Tiabi said. These were the first landmark steps toward a “Remodelled Prison Policy”.

In 2016, we took our cooperation to the next level by signing an EU-funded Twinning project between the Algerian Department of Prison Administration and its French and Italian counterparts.

The partners worked in three major areas: improving the prison administration’s central prison-management system, enhancing capabilities for providing support to convicts throughout the rehabilitation process, and strengthening security in prisons.

Marta Costantino, General Director at the Italian Ministry of Justice and head of the Italian side of the Institutional Twinning, considers that the aims of the project, which ended on 15 November 2018, have been achieved – and even exceeded. “The results of the twinning are highly positive. Cooperation between the three partners has been very close. We did not always agree – and that is a good thing – but we listened to each other,” she laughed.

“I think the addition of Italy’s input to the project was very useful, as the French and Algerian models are quite close, given the history between the two countries. We offered another point of view which I think it was beneficial for Algeria, as they are in the process of building its own system,” adds Marta Costantino.

Bruno Clément-Petremann, Marta’s French counterpart, believes that the institutional twinning creates a framework for exchanges that is beneficial for all the partners involved. “It is not about France and Italy coming in to tell Algeria how to do things. It is an exchange of professional practices between professionals. In fact, I can say that the Algerian prison system has strong points that would be interesting to see implemented in our own system, such as guidance and evaluation services across the board or experiments with predominantly agricultural prisons.”

An Effort to Abolish the Death Penalty

It is precisely this reformed Algerian prison model, which benefited from European expertise, that the country’s authorities wish to promote elsewhere in their corner of Africa. “We are ready to share our experience,” said Mokhtar Felioune to the directors of the prison systems in Chad, Senegal, Mauritania, and Burkina Faso, who were guests of honour at the conference. John O’Rourke, the European Union’s Ambassador in Algiers, welcomed this initiative: “We are pleased because the solutions implemented in Algeria may be a better fit for these countries, as they are based on broader regional specificities.”

This conference, organised two days before the World Day Against the Death Penalty, was also the occasion for O’Rourke to point out that Algeria has had a moratorium on capital punishment in place since 1993. “Having a humane and effective prison system is vital in working toward the abolition of the death penalty.” Since 1993, Algeria has succeeded in keeping a moratorium on capital punishment in place despite a difficult context [the fight against Islamic terrorism]. In this respect, Algeria deserves to be congratulated.”

The abolition of the death penalty would therefore be a logical next step in reforming the country’s justice system.