Learning about children’s rights through cinema: a European Union backed initiative in Morocco

What do cinema and human rights have in common? Their universal nature, and that members of The Association of Mediterranean Meetings of Cinema and Human Rights (ARMCDH) are eager to merge these two topics in order to spark children’s curiosity. The European Union is supporting this beneficial and necessary project in Morocco to foster a generation of youth who are aware of their rights and citizenship.

It has become a kind of ritual: each Sunday morning, around twenty children under 12 rush to the Les Étoiles Cultural Centre. In the centre of Sidi Moumen, an outlying neighbourhood of Casablanca, the ARMCDH organises screenings of animated films for local children. On the programme is entertainment and, above all, human rights education.

“I know that on the last Sunday of the month, there’s an animated film. It’s a great opportunity for our children to access these films. Of course, you can see them elsewhere, but it’s quite expensive. Here, they are free and close to home,” says a smiling Aziza, one of several parents who have come to drop their children off, just before eleven am. “They have fun and learn something,” she adds.

“Concepts that are useful to children,” explains Aziza. When interviewed, she bemoans a lack of children’s films in other cinemas. The films screened by ARMCDH, in partnership with the Les Étoiles Cultural Centre in Sidi Moumen, plug this gap.

Cinema as a means of understanding our rights

With this initiative, The Association of Mediterranean Meetings of Cinema and Human Rights (ARMCDH) have taken on a genuine challenge: how to combine cinema and entertainment with serious attention paid to human rights. Founded in 2010, the association is active in several cities throughout Morocco with the primary goal being, “to foster a culture of human rights through cinema,” says Ghita Zine, vice-president of the association.

Founded by Fadoua Maaroub, the association already runs several activities. Its “je dis” cinema (“I say cinema”) film screenings are open to the general public and take place once a month on a Thursday in the cities of Rabat, Casablanca, Tangier, Zagora and Agadir. There are also quarterly Master classes, during which well-known personalities from the world of cinema are invited to take part in debates and “Nuit Blanche” (sleepless night) events with an all-night programme of short and feature-length films concerning a chosen human right issue There is also a human rights short film night.

Drawing parallels between the universal nature of human rights and cinema, the association has quickly gained a considerable following. It all started in Rabat, where its headquarters is located, but rapidly expanded to other cities in Morocco including Kenitra, Casablanca, Tangier, Agadir and Zagora in the south of the country. Social class, level of education and socioeconomic status are rapidly eclipsed by one central focus: the human rights to which every citizen is entitled.

For children, the priority is human rights and citizenship education

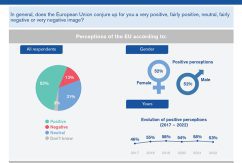

Since late 2017, the European Union has been supporting ARMCDH projects involving what Ghita calls, “cinema as a platform for human rights and citizenship education.” The main target audience: children.

The funding, which totals 300,000 euros over a 36-month period, enables the association to continue running morning screenings for children simultaneously in three cities: Casablanca, Rabat and Kenitra. Its ethos remains unchanged: free access to quality films.

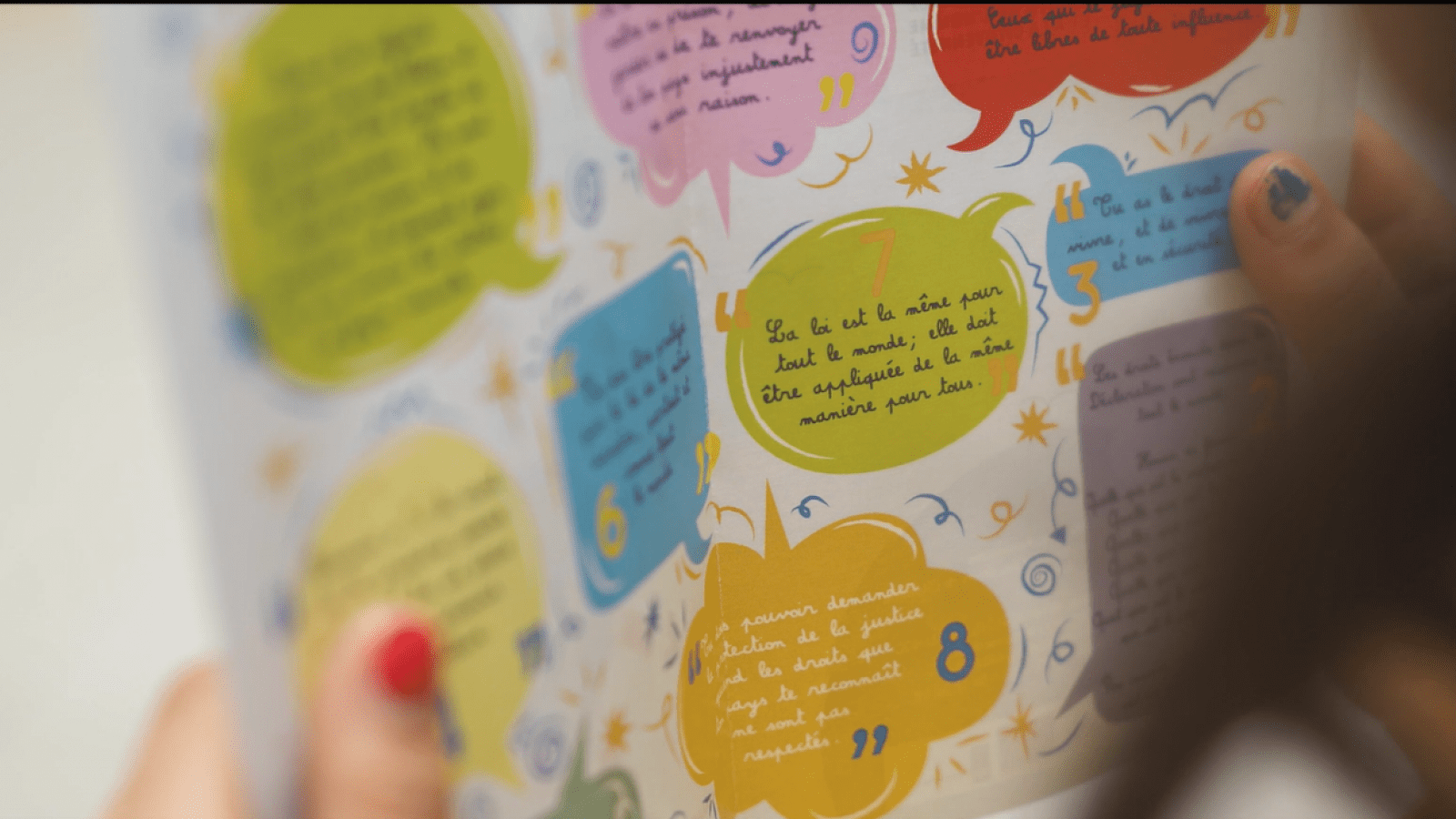

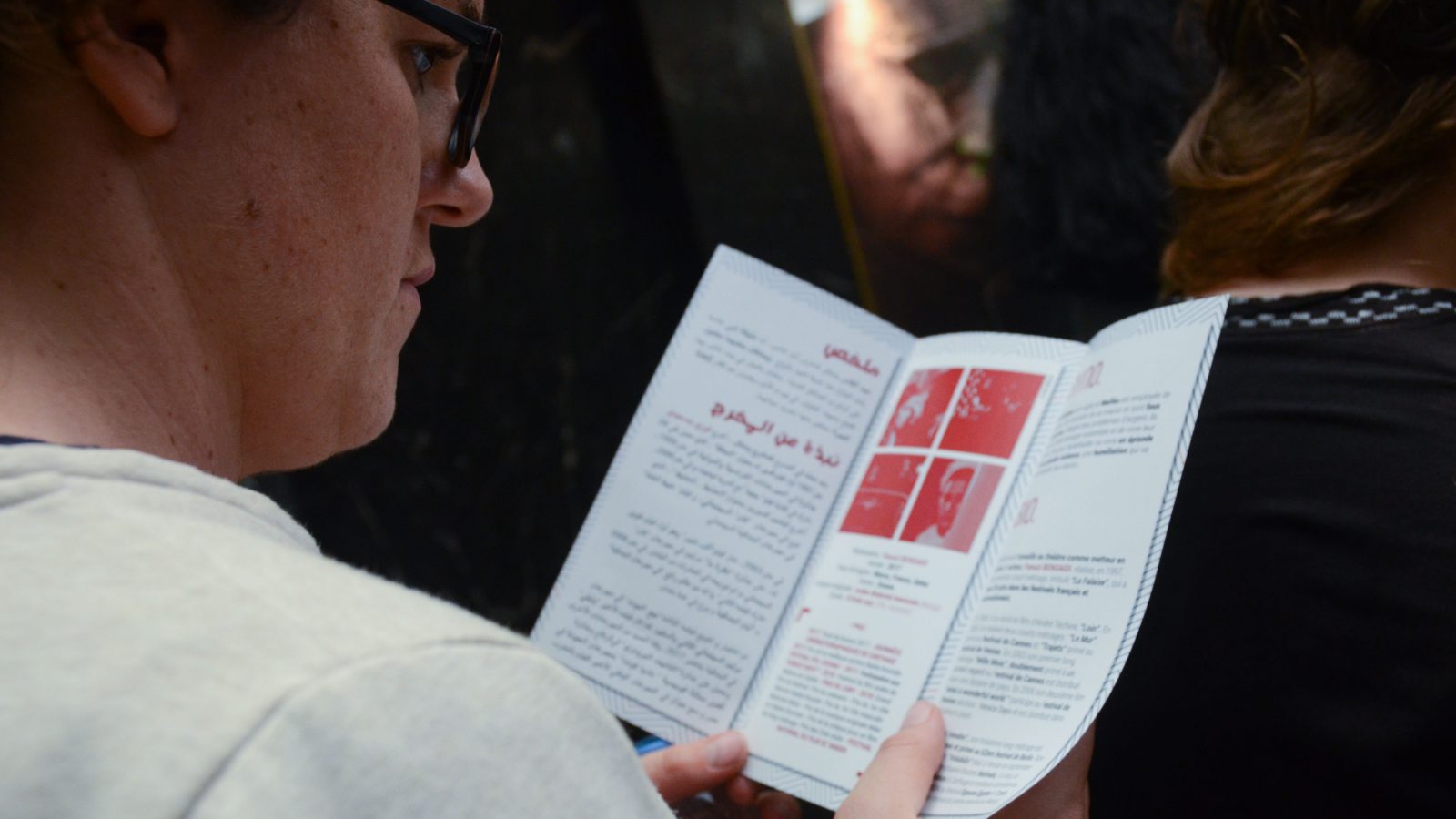

This morning, a few minutes before the projection begins, a paper is distributed among the children. It contains various children’s rights, which the young viewers are then asked to keep in mind while watching the animated film. “When we get home, I always talk to her about it and she tells me what she’s seen, learnt and taken on board,” says Latifa, another mother, speaking about her daughter. Hamza, aged 11, who has just been dropped off by his father, is another regular. “I come here to see my friends too. We all meet up in this room to play before watching the film together,” he explains shyly, under the watchful gaze of his father.

The slip of paper in question is a “children’s rights passport”, produced by ARMCDH, in partnership with the European Union. “The idea is that they get one of these before the start of each screening. We ask them to hold onto it so they can start developing an understanding of children’s rights,” says Ghita, going on to explain that, “it acts as a starting point for the discussion after the film screening.” Ghita, a journalist from Casablanca who is also on the board of the association, leads the post-film discussion. “Lots of the children come regularly and are starting to get used to the routine. Some of the children are quick to speak up with any words or phrases I may have forgotten when explaining what we need to do,” she laughs.

The programme is curated by the ARMCDH board and volunteers, which include current and former teachers. “For these matinées, the children themselves play a big part in choosing the films. This helps spark discussion afterwards,” explains the vice-president of the association.

Another European Union backed initiative is the creation of film clubs in the school setting. “We have started training teachers and heads at state secondary and high schools that already have a citizenship club,” explains Ghita. These supervisors are then invited to “encourage their students to watch films more often or even organise their own screenings.”

Fact sheets are then created using a body of human rights texts such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Convention on the Rights of the Child.

A valuable project for neighbourhoods like Sidi Moumen

In Sidi Moumen, parents unanimously agree that the ARMCDH screenings are beneficial. Just a few kilometres from central Casablanca, this neighbourhood is considered disadvantaged.

Mainly composed of slums, it gained tragic notoriety in 2003 as the birthplace and childhood home of the eleven suicide bombers involved in the 16 May 2003 attacks against various tourist sites in Casablanca. A few years later, several initiatives were launched to rehabilitate the district and combat social exclusion, and the Les Etoiles Cultural Centre was part of this effort. It owes its name to the book by Mahi Binebine, “Les Étoiles de Sidi Moumen” (The Stars of Sidi Moumen), which revolves around the lives of the eleven perpetrators of the 16 May bombings. A runaway success, the book was soon adapted for the big screen under the title “Horses of God”, directed by Nabil Ayouch, who dedicated the film to the neighbourhood.

“With the money from the film and the book, Nabil Ayouch and I decided to launch a cultural centre to offer young people in the district a different life to that of their infamous predecessors,” explains Mahi Binebine. This led to the foundation of Les Étoiles Cultural Centre, offering young people in the neighbourhood the chance to take part in dance, music and art workshops, and, thanks to ARMCDH, attend screenings of children’s films with a focus on human rights.

This morning, a few metres from the projection room where the children’s eyes are fixed on the screen, a mother patiently waits for her ten-year-old daughter. “It’s never easy for young people to find something to do in a neighbourhood that’s isolated from the city centre. And it takes time and money to get there,” she laments. “My daughter often comes here for the dance classes and the Sunday morning screenings. As well as watching a film, she has the opportunity to discuss it with other children her own age and share her opinions,” says Latifa who, in just a few words, tells us all we need to know about the importance of cinema.

EU Neighbours Links

EU Delegation