Kolea: A Hub for Prison Reform

This year marks the 10th anniversary of cooperation between the European Union and Algeria on prison reform. It was the occasion for the Department of Prison Administration and Rehabilitation (DGAPR) to organise a visit to Kolea Prison – one of Algeria’s most modern prisons – and the National Academy for Prison Administration Employees.

“Welcome.” This little hand-painted sign appears odd. Attached to heavy steel bars, it signals the entrance to the women’s ward of the prison located in the small town of Kolea, 40 kilometres west of Algiers. Today’s visitors include representatives from the prison systems of European and African countries, representatives from the European Union, ICRC members, and journalists. Upon entering the ward, they travel down a long corridor bordering an open-air sports field.

Inmates are getting some exercise on the artificial grass pitch under the supervision of a female instructor. “The prison boasts several sports fields – one for each ward,” says Chaouchi Ahmed, the prison’s warden.

The delegation crosses through a buffer zone made up of two heavy armoured doors, then arrive in the prison area specifically reserved for studies and activities. The teaching and training programmes are adapted to the skills of each inmate. For instance, they can participate in hairdressing, stitching, and sewing workshops, reading and literacy courses, and many others.

The ward’s superintendent offers a few additional details: “Our goal is to do more than just keep inmates busy. We want to make sure that they get the knowledge they need to successfully return to society when they are released.” Here, diploma-granting training courses are taught by teachers working for the Ministry of Occupational Training.

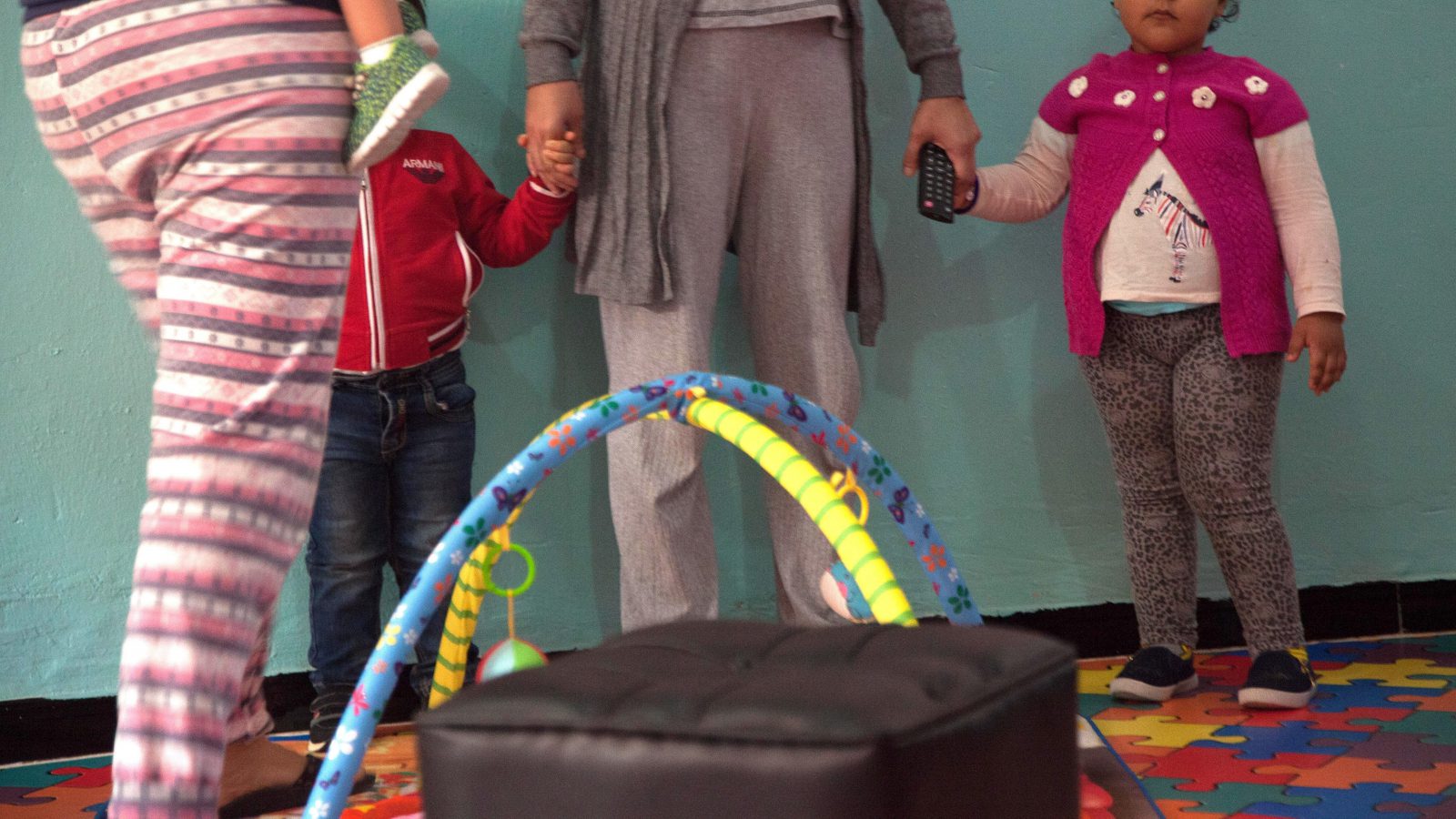

The camera flashes make some of the inmates feel uneasy. They lower their heads. An official from the Ministry of Justice repeats the instructions given to photographers at the start of the visit: “To preserve the dignity of our inmates and their families, frontal photos are not allowed.”

The prison encourages reading through a policy that rewards inmates for each book they read. “Whenever an inmate finishes a book, he or she is asked to write a book summary. A prison official reads the summary and eligible inmates are granted permission to leave for a short period of time or receive an increase in the length of family visitation hours,” the warden explains.

The visit continues to the next floor. Another long corridor leads to dormitories, each with 10 beds. Each dormitory has a bathroom at the back, which consists of a toilet stall and a shower with a shared sink tucked in between them. The dormitories are clean, and there is a strong smell of cleaning products. The inmates’ personal belongings rest on a small shelf built into the foot of each bed. Their personal lives are summed up in a few square centimetres: a bar of soap, pictures of friends and family, small paintings, etc.

Child Care and Nursery Facilities

The delegation heads down a flight of stairs and enters a place filled with emotion: the wing set aside for mothers and their children. Women who give birth in prison have the right to keep their babies with them for three years. Newer prisons have child care and nursery facilities built within their walls, allowing female inmates to raise their children in “proper conditions”. There is a refrigerator, a washing machine, and hot water. The prison handles vaccinations and provides baby formula and nappies. When children reach age three, they are placed in the care of their families or in centres run by the Ministry of Solidarity.

The Advocate General of the French Court of Cassation, Philippe Le Maire, explains that in France, female inmates are only allowed to keep their babies for 18 months. “In Algeria, mothers traditionally breastfeed their babies for two years. Studies have also shown that babies need permanent contact with their mothers until at least the age of three,” says Slimane Tiabi, Educational Director of the Department of Prison Administration and Advisor on the Algeria-Italy-France Institutional Twinning funded by the European Union to provide “assistance in strengthening the prison administration”.

An Algerian Experiment

The delegation now heads over to the minors’ ward. Minors also fill their days with reading courses, training sessions, and sports activities. In one classroom, a group of young people are taking literacy courses. Officials from the Ministry of Justice point out that, thanks to the reform, prisons now give inmates the opportunity to graduate from high school and engage in university studies. Statistics have shown as well that convicts who graduate from high school during their time in prison do not go on to become repeat offenders.

In a game room, young people enjoy friendly games of pool or table football. The unanticipated arrival of a group of strangers seems more entertaining, and some stop to strike a pose for photographers – from behind, of course, to comply with prison officials’ instructions on photos. Many are in prison for drug-related offences, which has led prison officials to organise campaigns to raise awareness about the dangers of using and selling narcotics.

For Abdoulay Cherif Djorok, the head of Chad’s prison system, “Algeria’s experiments can be a positive example for prison policy. During my stay in Algiers, I have had the opportunity to see innovations and concepts that we might be able to implement in Chad in terms of prison conditions, rehabilitation conditions, and prison management. Our government understands that prison conditions need to be improved and believe we can benefit from Algeria’s experience.” He is of the opinion that it would be possible to launch a programme to implement the experience gained in Algeria within the context of a three-way partnership between the European Union, Algeria, and Chad. “The EU is already involved in Chad through the PRAJUST project (Project to Support the Justice System in Chad). This three-way partnership could be used to further support the prison reform process.”

Employees in Mustard-Yellow Uniforms

The visit continues inside the ward reserved for workshops for adult convicts. Most are wearing a mustard-yellow uniform, which is mandatory for all convicts whose sentence is definitive. The first workshop is a veritable small-scale shoe factory that crafts shoes for the prison staff. The inmates are employees paid by the National Bureau for Educational Work and Apprenticeship (ONTEA), which sells these shoes to the prison system. “They are entitled to wages and social security. The money they earn is put in a bank account for them. They can use it to buy things for themselves or send money orders to their relatives,” explains the prison warden.

Our visit ends in the concert hall, where musicians in mustard-yellow garb are playing Ya Rayah (You, the One Leaving), an Algerian song made popular the world over by Rachid Taha.

As representative of the French public interest group Justice Coopération Internationale, which participated in the implementation of the EU-financed Institutional Twinning, Philippe Le Maire shares his initial impressions: “I am very impressed by what I have seen in Kolea. This is a prison that meets the highest international standards. The prison conditions are up to par. Our Algerian friends have done a truly remarkable job. The Kolea prison is the only one I have visited. Now, the rest of the prison system has to be modelled after Kolea.”

A Benchmark for Excellence

The delegation leaves the prison and heads to the National Academy for Prison Administration Employees (ENFAP), also located in Kolea. Founded in 2015, the ENFAP trains prison employees, sergeants, and officers, and provides continuing education courses in a variety of areas such as detainee management, judicial records, working with minors and vulnerable populations, and rehabilitation.

The Academy, seen as a benchmark for excellence, has also played an important role in implementing the Algeria-Italy-France Institutional Twinning that provides “assistance in strengthening the prison administration”. “We have hosted several training sessions from this European Union programme in areas such as prison management, sentencing, and inmate categorisation,” explains ENFAP Director Abdelhak Belamari.

Slimane Tiabi, Educational Director of the Department of Prison Administration and Advisor on the Algeria-Italy-France Institutional Twinning, feels that the prison reform process, which the European Union has played a major role in supporting, has achieved its main objectives. “Today, respect for human dignity is a constitutionally guaranteed right. Inmates commit crimes, are prosecuted in accordance with the law, and are sent to prison, but they are still treated with the dignity they deserve. This means that the basic rights of convicts are respected. The widespread cliché is that prisons are just places where we lock away prisoners. Today, prison is more than that,” he insists. In his opinion, the Algerian government’s reforms “can prepare inmates to return to society”.