DIVECO 2 : Caught up in the nets mended by the women of Cherchell

Launched in 2015, the Programme to support diversification of the fisheries sector’s economy-DIVECO 2 has the aim of increasing the economic diversification of Algeria through sustainable development and the improvement of economic performance in the fisheries sector. The programme was organised around a set of activities for the benefit of stakeholders in the fisheries and aquaculture sector, focussing on the strengthening of professional organisations and groups, sanitary control, port management, shellfish farming and even the evaluation of the national legal framework. Diveco2 has made it possible to implement several support projects in very specific areas, including net mending.

‘Training women to mend nets was initiated after an assessment of net repairing activities. Experts from the programme led a socio-economic study of this specific occupation in 28 ports and fishing shelters’, explains Nadia Bouhafs, National Director of the Diveco2 Programme. The study raised the question of renewing the profession and the need to implement a training programme. ‘With a fishing school and a major port, Cherchell was chosen as the pilot region for launching this training. The role of net mender is essentially a male one, but the opportunity to train women came to fruition because there was a real demand. The idea was to share this profession by training female net menders who would then become trainers in turn,’ adds Nadia Bouhafs.

‘Get your feet wet…’

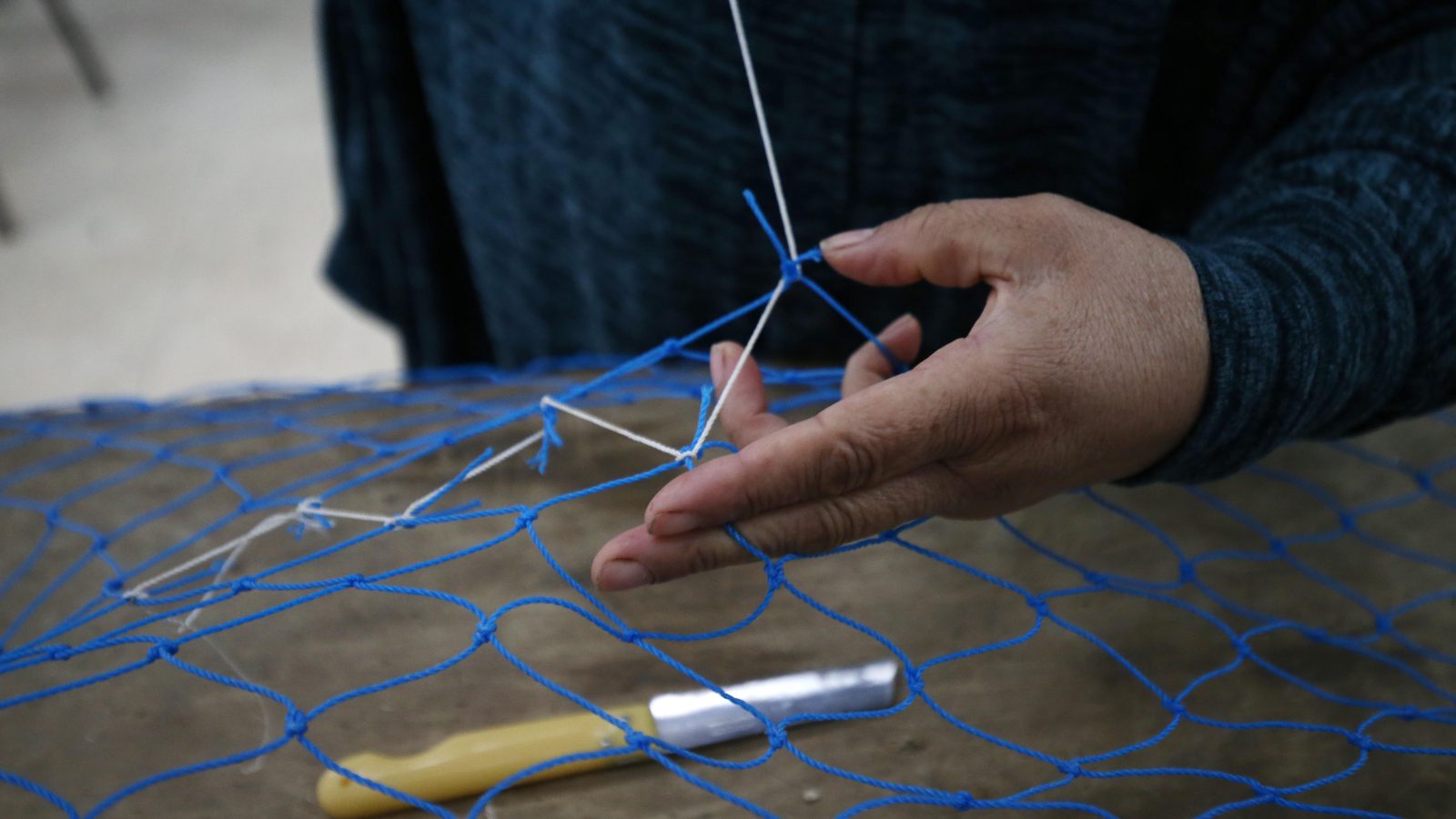

Karima Daïkhi is proud of her rough hands. This 53-year-old mother runs the big, flat needle through the mesh of the fishing net, makes a knot and cuts the thread with a snip. With a smile on her lips, she mechanically repeats this gesture, watched by Bouchra Salah, a teacher at the Cherchell Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Training School.

Karima is a net mender. She is one of around 30 women from the region who have mastered fishing net repair techniques. Her life, marked by tragic episodes, is closely linked to the sea. ‘My husband owned a trawler in Cherchell. He was murdered by terrorists in 1994. In fact, I still don’t know how I escaped death that day,’ she says.

Overnight, the life of Karima and her children was turned upside down. The young mother, who had never worked before, had to roll up her sleeves to feed her children. She then went from odd job to odd job. ‘One day, I went to see my husband’s family, to ask for the monthly share of the fishing which rightfully should have gone to our children. His brothers refused. They just told me: ‘If you want to eat fish you have to get your feet wet.’

Taking them at their word, Karima set herself a challenge: to become a deep-sea fisherman. ‘In 2006 I went to the Fisheries School with my eldest child. I told them my story and they allowed me to train as a sailor.’ The mother and son managed, with brio, to get their booklet, that magic key allowing them to go to sea aboard a fishing boat. Karima returned to the school in 2016, to attend the net mending training course initiated as part of the Programme to Support Diversification of the Fisheries and Aquaculture Sector’s Economy (Diveco2). ‘Today, my children have their own boat, an “espadonnier” (swordfish catcher), as we call them here. As for me, I take care of mending the nets. I remain convinced that it is possible for us, women, to make a good living by practising this very profitable, full-time activity,’ Karima insists.

Feminisation of the activity

Wahid Salah, director of the Cherchell Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Training School, actively participated in the involvement of women in this training programme. ‘In the past, it would have been the fisherman’s wife who repaired the net when he came back from sea. But this was within the family environment. In Algeria, net mending is still practised in a traditional way, on the quayside. The port remains a masculine place, but it is possible to arrange spaces to allow female net menders to work without being self-conscious,’ he says. A real fishing professional, Wahid Salah believes in the feminisation of the net mending activity. ‘The development of the fisheries sector needs the net mending activity to be professionalised. Tying knots is not enough to repair these fishing tools. You still need to master certain techniques so that they remain effective even after repair. Women are generally patient and conscientious and those are the two essential qualities needed in a net mender.’

A fruitful experience

Malika Salhi wants to make net mending her profession. A seamstress by training, she is encouraging her friends who have followed the training to create a net menders’ co-operative. ‘Thanks to Diveco2, we were trained in business creation and management. Ideally, at this stage, we should come together and create a co-operative. This way, we could use our knowledge and provide quality services to the region’s fishermen. Demand is very important. Some fishing bosses come from very far away to repair their nets as the workforce is non-existent in their region.’

Nadjet Belhoundja also supports the idea of creating a net menders’ co-operative. ‘It’s a profitable project but we can’t afford to get it back on track. Ideally, we would have a workshop near the port to be able to work between women. To achieve this, we need to join together and prove our commitment. It’s not easy because we are housewives and don’t have experience in entrepreneurship,’ says Nadjet.

Hope and determination

But hope is still possible, especially as Cherchell’s port could soon become home to the first totally female net mending space. This was the idea of Abdelkader Chenaa, master net mender, who approached the National Ports and Fishing Shelters Company to obtain space for setting up this workshop. ‘I recently learned that the Cherchell Fisheries School had trained female net menders. This is a valuable workforce and a good work opportunity.’ Abdelkader receives nets from many parts of the country, he admits that he is often overwhelmed by orders. According to him, a good net mender can earn up to 100,000 Algerian dinars per month (around 500 euros).

Net mending: perpetuating the success

The success of the net mending activity and the training of women in Cherchell encouraged the Directorate-General for Fisheries and Aquaculture (DGPA), a beneficiary of the EU-funded Diveco2 programme, to replicate this experience. In Beni Ksila, female net menders have also been trained and have been in business for a few months. In Jijel, people with disabilities have benefitted from the same training and are now mastering the art of repairing nets. But what about Cherchell’s female net menders? They have not been forgotten. The DGPA plans, in fact, to support them in their efforts to create their own co-operative. ‘We plan to support this group of women trained at the Cherchell Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Training School with the aim of creating a profit-making network. They are able to participate, actively, in local, sustainable development and support the development of fisheries and aquaculture in this region. As an official institution, we must make our contribution to facilitate the professional integration of these women,’ says Taha Hammouche, Director General of Fisheries and Aquaculture.

In Cherchell, as elsewhere, the professionals of the sea know that success of a fishery depends largely on the work of the net mender. A badly repaired net can compromise a fishing operation. Karima, Malika and Nadjet are aware of this. Cherchell’s net menders are ready to face this heavy responsibility.