Wastewater treatment: the EU and UNICEF wade into the Lebanese swamp

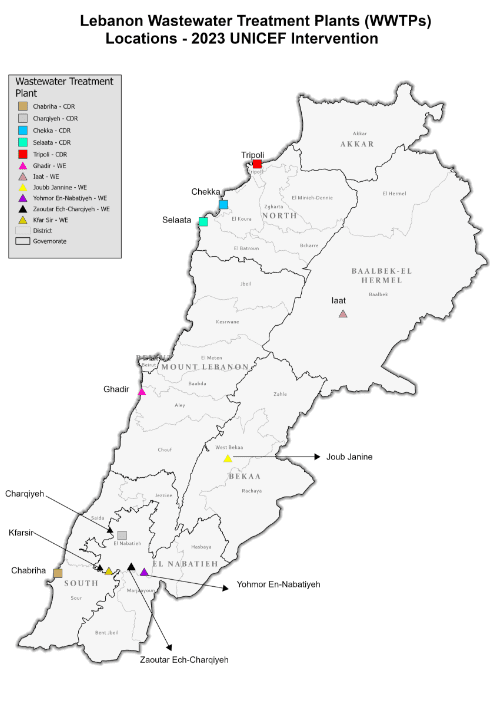

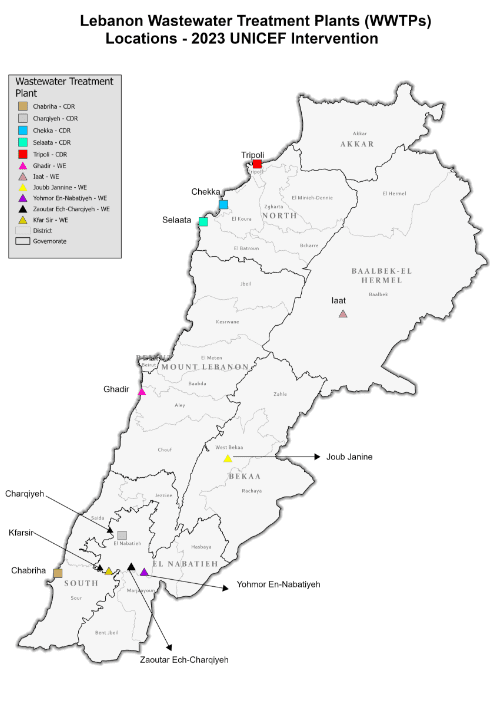

Between now and 2025 eleven wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) should once again be fully operational in Lebanon.

Lebanon could well lose its title of “Water Tower of the Middle East” due to the continued absence of public policies to protect this resource. In a context of multi-dimensional crisis including financial collapse and power blackouts, the country’s wastewater treatment situation, which was already critical, has gone from bad to worse in recent years. Of the more than 70 WWTPs throughout the country, 28 of which are considered major by their capacity and the population they serve, only a few remain in operation, and then only at their minimum operating level.

This state of affairs is well known but neglected by the Lebanese authorities. The Country Office of UNICEF, the United Nations Children’s Fund, drew attention to it on numerous occasions last year, when a cholera epidemic spread through certain regions of the country, mainly affecting the most disadvantaged populations. In order to get things moving again, on the occasion of World Environment Day on 5 June last, the Ministry of Energy and Water announced a partnership with the European Union and UNICEF in connection with its plan for the revival of the water sector by 2026.

Financed by Brussels and implemented by UNICEF, this project aims to restore 11 WWTPs to operation and bear their operating costs between now and 2025. To finance this operation, the EU siphoned off €30 million from the total budget of €179 million earmarked in 2022 for aid to the Syrian refugee crisis in Lebanon. “The problem of water treatment concerns everyone in Lebanon,” explains Alessia Squarcella, deputy head of cooperation in the EU delegation to Lebanon.

Of these 11 plants, five are on the coast – at Chabriha, Ghadir, Selaata, Chekka and Tripoli – and six inland – Iaat, Joub Jannine, Yohmor-Nabatieh, Zawtar El Charkiyeh, Kfar Sir and Chariyé. The coastal plants are only active from May to October and only filter out solids (primary treatment), while the others purify the water 90% (secondary treatment). As for tertiary treatment, in which all traces of pollution are removed from water, Lebanon does not have the necessary infrastructure for this, with the exception of the Zahlé plant, Beqaa Governorate.

This project should also allow responsibilities to be transferred among public institutions. According to a law passed in 2002, wastewater treatment should be a task overseen by the Ministry of Energy. However many WWTPs are under the control of the

Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR), a public establishment that has overseen major State projects since the 1990s. “The CDR built most of the plants, so they remained under its control. This no longer makes sense today,” the EU delegate continues.

Making the sector self-sufficient

Other aid projects are being discussed in Brussels, but the EU is clear: the Lebanese authorities will take back control as soon as possible. “We don’t want to create dependence. We’re supporting the Lebanese State because the situation is exceptional, but we’re not going to replace it,” Alessia Squarcella assures us. “The aim of this operation is to make the water treatment system self-sufficient. ”

The departing Minister for the Environment Nasser Yassine shares this position. “In parallel with this aid, we should redouble our efforts to ensure the continuity of this project by means of a system for recovering disbursements while at the same time reducing operating costs at the treatment plants, solar energy being an obvious example,” he declared in the project press release published on 5 June by UNICEF.

The breakdown of wastewater treatment is in fact just the tip of the iceberg: other parallel reforms are essential. The WWTPs depend on the electricity produced by the power plants, whose tariffs have sky-rocketed since the crisis of 2019. “With the increase in electricity charges, our budget could not cover the whole country. We selected plants in consultation with the Ministry of Energy based largely on the impact non-operation of these plants would have on the country’s public health, environment and economy,” says Alessia Squarcella. It is therefore up to the Lebanese State to invest more, and better, in the energy sector.

Risks to health

The cholera epidemic that broke out in October 2022 in Lebanon, and which officially ended in June according to the Ministry of Health, is the most tangible proof of the dangers involved in a lack of water treatment for the population. This disease, which is transmitted by contact and by ingesting food and water contaminated with faecal matter, caused 23 deaths among the 8,000 suspected cases recorded.

Besides, when the system collapses, the most obvious result is seen in the interruptions in water supply, but the hidden consequences are every bit as bad. Households have to resort to private tanker trucks to transport water. While not legal, these are tolerated, and they escape health controls. Some vehicles are open-top, exposed to bacteria and pollution. And this impure water is much more costly than the water that could be supplied by the State.

Lastly, the dangers to health do not concern only the direct consumption of water. Wastewater is discharged into the rivers that supply water for agricultural irrigation.

This article is the result of a collaboration between the EU Delegation Lebanon and the media L’Orient – Le Jour. Link to the original article: https://www.lorientlejour.com/article/1345084/traitement-des-eaux-usees-lue-et-lunicef-mettent-les-mains-dans-le-marecage-libanais.html